The book is 428 pages and has 176 maps, figures and tables. Availabe at all Amazon sites.

Visit my home page www.pestcontrolsupertech.com

Based on 895 literary sources published in 18 European countries, the Americas, Africa, Asia and Australia during the last 400 years, this book exposes the unreliability of using current hypotheses handled in stochastic models to explain the spatiotemporal development in bird populations, compared to the reliability of using historical, empirical material, exemplified by the Ortolan bunting Emberiza hortulana.

The author compared factual historical information about the development and status of the population to current theories, which are based on recently collected data in contemporary research.

Large knowledge gaps were discovered in the understanding of the development and dynamics in the population across the distribution range.

The review also debunked myths now used by researchers as verified scientific data to support current views on ortolan bunting ecology and population trends.

In addition, the historical literature showed that scientific projects recently run in Europe to reveal aspects of the Ortolan bunting's ecology, produced results already known from data collected from 90 to 190 years ago.

This exercise is an example of the advantage of extracting historical, empirical hard data on bird species in general, to better understand spatiotemporal population dynamics not possible to discern by transitory, geographically disconnected tests in current environments.

Current theory posits that the Ortolan bunting is declining due to human influence through fragmentation of habitat and illegal hunting, especially in France. The fragmentation results in a scattered and "island"-like distribution in Western Europe.

However, the Ortolan bunting is distinctly a valley colonizer and the distribution is due to site selection during colonization, not habitat fragmentation.

The bunting breeds on the exact same "geographical islands" today as it has done throughout the last 300 years - and it also does NOT breed in the same areas it did NOT breed in, during the same period.

To superimpose the largest rivers in Europe on a distribution map illustrates the dynamics. 1: Rhine. 2: Main. 3: Ems. 4: Weser. 5: Aller. 6: Elbe. 7: Havel. 8: Spree. 9: Vltava. 10: Elbe (within the Czech Republic). 11: Oder.

White circle: Positive information about absence. Black open circle: Rare. With one crossbar: Common. With two crossbars: Very common.

In the book, 8 maps show the European observation material in time periods from 1724 to 1900.

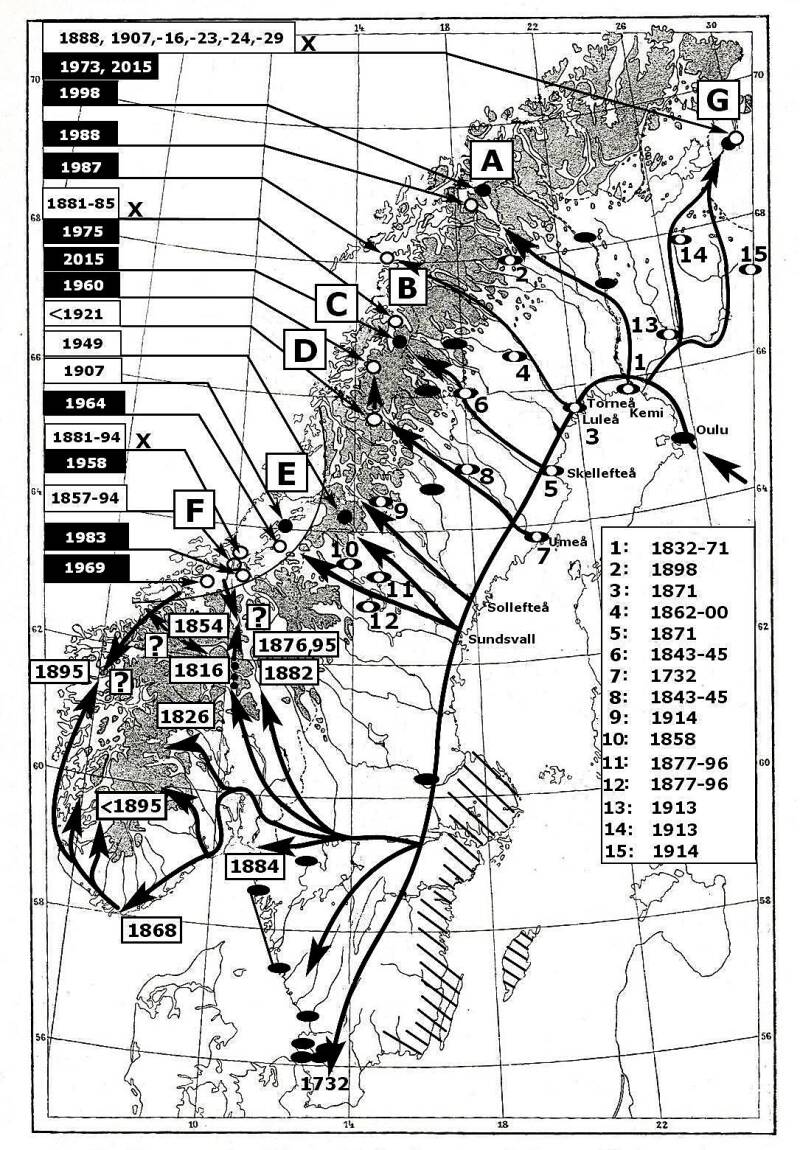

The Ortolan bunting expanded from an origin in Western Asia/The Mediterranean and colonized Western Europe via the river Danube, spreading out in the rest of the West- and Central Palearctic regions through other major river valleys. 1: Po. 2: Danube. 3: Dniester. 4: Dniepr. 5: Don. 6: Volga. 7: Ural. Currently the population center is located in Russia as a result of asymmetric growth and this center serves as a source of emigrants to Western Europe.

Current researchers claim that the population in Fennoscandia suffer from increasing isolation due to lack of contemporary gene flow from Western Europe.

However, the bunting colonized from the Volga-Baltic Waterways in the southeast, through Finnish Karelia, continuing south and west after it had rounded the north end of the Bay of Bothnia. It penetrated the mountain barrier between Sweden and Norway through river valleys with low level passes, indicated by a very limited number of known breeding sites in Northern Norway linked via specific valleys to source populations along the Swedish east coast, where that country's population is most abundant.

This historic linkage can still be observed today, with new discoveries at the same sites in Northern Norway, but nowhere else.

Researchers also have the impression that that the bunting avoids coastal areas. This opinion arose from the fact that ornithologists in the 19th century claimed that it did not breed in Western Norway, and it was later explained by a 1948 publication stating that the bird has a preferance for areas with less than 600 mm annual precipitation.

However, from the 1850s to the 1890s the ortolan bunting was distributed along the entire Norwegian west coast north to 67.6 degrees. At one of the locations (Førde), with an annual precipitation of 2.780 mm, it was described as "one of four characteristic species in the valley". Simultaneously (1893) it was found breeding on grass covered islands in the Guadalquivir marsh Las Marismas on the southwest coast of Spain, 27 degrees 51 minutes further west than the locations in Northern Norway.

By 2019, the Ortolan Bunting population - in the 1890s stretching 270 miles across the entire South Central Norway - had retracted eastwards to a small patch with 6 pairs on the Swedish border.

Hemsila River by Gol Church at the intersection of the Hemsedal and Hallingdal valleys in South Central Norway in 1890. This is the habitat where Swedish naturalist Sven Nilsson discovered the most abundant population of ortolan bunting he had ever encountered in Scandinavia, in 1826. There is no reason to believe that the area had undergone major changes during the 75 years before 1890. The arrow points to the road to Gol Church, just outside the picture and specifically mentioned by Nilsson as a high density location.

Ål, Hallingdal Valley, South Central Norway in the early 1900s, 15 miles west of Gol. This is the second location Sven Nilsson brought up as having the most abundant population he had ever encountered in Scandinavia. It was monitored by four ornithologists across the following 200 years, all but one with doctorates in zoology, and in less than 112 years the popuation decreased to zero. The habitat is typical - mountain slopes facing south, exposed to intense sunshine which creates an overpowering heat at ground level.

Another breeding location with a typical habitat in South Central Norway - Vestfjord Valley near Rjukan. The observation of Ortolan Bunting was made in 1895 and the picture taken in the early 1900s. The English naturalist Abel Chapman and his brother had arrived to enjoy trout fishing in the river Måna (picture), but stated that - "The midday heat was so intense, we could only fish in the morning and evening". During the day they recorded bird- and insect life on the mountain slope.

The same mountain slope in the Vestfjord Valley in 2024 where the Chapman brothers disovered the Ortolan Bunting in 1895. There is no reason to think that the habitat has been impacted by negative anthropogenic effects as the slope is a risk area for rock and soil avalanches which previously wiped away bridges and roads on several occasions. Hence it is impossible to utilize for forestry or agriculture and it is now part of a nature reserve - but it has no recorded observations of Ortolan Bunting the last 130 years. (Google Maps)

The reduction of the ortolan bunting population in Norway has been linked to the biocidal effects from mercury laced seed grain, specifically in conjuction with the "tractorization" of agriculture. Higher speed with tractor than with horse drawn implements during sowing led to more spill accessible to the bird. The introduction of "the Little Grey Fergie" tractor with a rear-mounted three-point linkage which could lift the seed drill from the ground (even more spill) has been blamed.

The abandonment of the old burning of grass and brush has also been suggested as a reason why the bunting declined, as it could have been dependent on such a reduction of succession in the habitat to the lowest possible level (fire burns).

However, the most abundant population Swedish naturalist Sven Nilsson ever recorded during his year-long excursions in Scandinavia (picture above, Ål) in South Central Norway in 1826, fell to zero in 112 years - and from "common" to zero in 40 (figure above).

This decrease is one of the fastest and most dramatic in Scandinavia, and it happened while grass- and brush burning was still common, before the tractor was introduced, i.e. the three point linkage had yet to be invented, sowing and harvesting was done either by hand or horse drawn implements, no mercury laced seed grain was in use and no plausible reason can be found to suspect destructive habitat fragmentation on a region wide scale from human activity.

The perception of a unidirectional declining trend in the ortolan bunting population in Europe has emerged from data collection over an insufficiently long period of time. This population needs to be viewed across centuries and the whole continent - and this may very well be the case also with other bird species. 10-40 years will only give a glimpse into the current trend, but not show the whole picture.

The bunting has always been famous among European ornithologists for drastic, unpredictable, inexplicable shifts in distribution and habitat use, with colonizations and subsequent retractions of the periphery across 60 - 100 years. In the picture on the left a very noticeable colonization and retraction, commented on by multiple ornithologists, took place north to Lorraine between 1760 and 1822 where the bird stayed for more than 60 years. By 1855 the population had retracted south of a a boundary running from the river Adour (west) to the river Durance (east), passing the Cevennes Mountains and Lyon. By 1878 the Ortolan bunting was found almost exclusively within the old province Languedoc in the southeast of the country, and was unknown further north.

The picture on the right illustrates movements in the French population throughout the last 260 years, according to information in literature.

The population in Fennoscandia behaves according to the principles in the Abundant Center Hypothesis. There is an exceptionally high immigration rate in Europe from the source population in Russia, and there is reason to believe that the variation in this rate over time has decided the fluctuations and trends in Fennoscandia and the rest of Europe, and hence where the periphery has run at any given time.

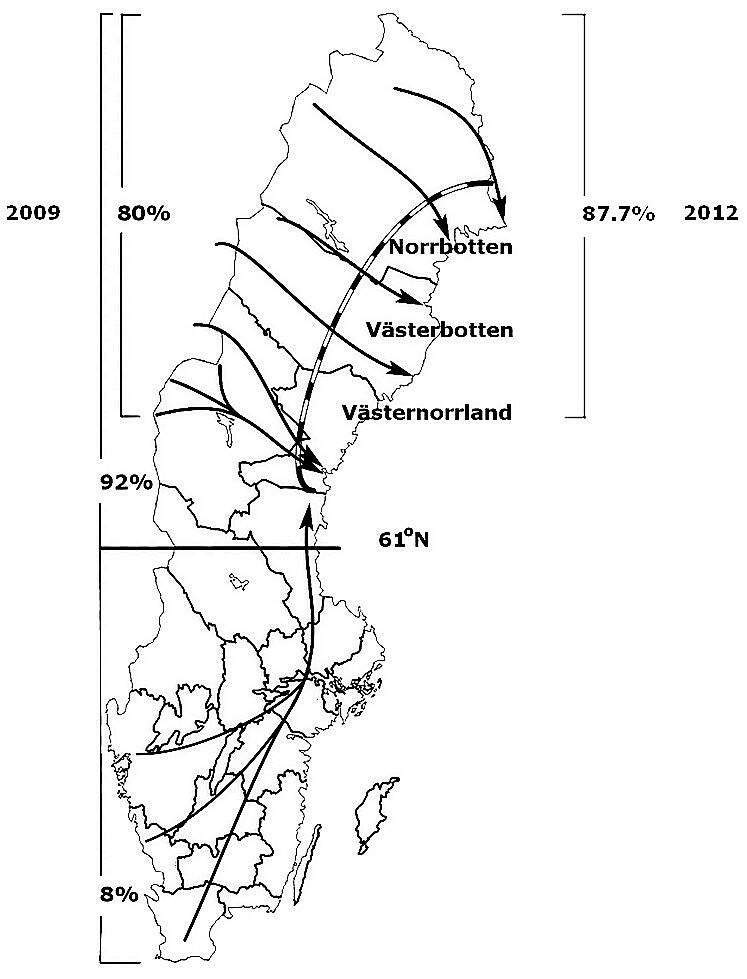

During the population reduction in Fennoscandia throughout the last 50 years, the gravitational center has moved increasingly further north in Sweden and around the Bay of Bothnia back into Finland - backwards along the original colonization route from Finnish Karelia.

In 2009, with a Swedish population estimated at 6.300 pairs, 92% was situated north of the 61st parallel, 80% in the three northernmost counties. In 2012 the national estimate had decreased to 3.700 pairs - and the proportion in the three northern counties predictably increased to 87.7%.

A review of the the range boundary over the last 227 years from 9 different sources (A - I) gives the distinct impression that the eastern part of the range is as broken up as the western - it is just lacking in detailed information.

The eastern boundary has expanded eastward due to deforestation of the Russian Taiga and the Ortolan Bunting has moved succesively off the steppe onto the forest clear cuts, a behavior recently also recorded in Northern Sweden.

The boundary has moved more than 1000 miles (from A to I), equal to the distance from the Dutch coast to Western Ukraine - i.e. across the entire Western- and Central Europe (arrow).

Consequently, there is a strong indication that the decrease in Western Europe since the record abundance in South Central Norway in 1826 has been due to natural causes, not to negative anthropogenic effects. Asymmetric growth has moved the western boundary eastward, giving the appearance of a population "going extinct".

It has been claimed - and is still claimed both in current scientific literature and on popular sites like Wikipedia - that 80.000 - 200.000 Ortolan buntings were captured in Cyprus every year and exported to Europe as delicacies for the table. This myth was debunked by the German ornithological pioneer Johan Friedrich Naumann already 200 years ago, in 1824. It was reconfirmed as a myth in 1911, and later observations (1968, 2003-2013 and 2021) have also reconfirmed that this is incorrect. All small birds caught for the table were labelled "ortolans" and the author found 34 species and subspecies which had been assigned this name.

The French ornithologist Toussenel described how he was met by the bird catchers of Marseilles in 1859, when claiming that they mislabelled the different species and pointing out that they had Greenfinches Chloris chloris, Chaffinches Fringilla coelebs and Common Linnets Carduelis cannabina for sale:

"That may be true in Paris (his home town) but here in Marseilles, they are all ortolans".

A summary of accounts of bird catches from Italy, Germany and France from 1611 to 1885 (274 years) showed that of 409.500 birds taken during 51 seasons, only about 600 were actually ortolan buntings - 0.15%.

An estimate of average, annual catch between Recanati and Falconara on the northeast coast of Italy in the 1880s, made by "the best experts among the bird catchers" upon request from Italian ornithologists. The proportion of Ortolan bunting among 173.200 birds was 0.17%, virtually identical with the proportion in the combined catches from Italy, Germany and France 1611-1885.

According to current scientific literature an average of 50.000 (maximum estimate 100.000) Ortolan buntings were caught annually during autumn migration in southwest France, especially in Department Landes (picture on left).

It was claimed that this hunting was unsustainable in a European population perceived to be in decline and that the Fennoscandian population, migrating through the hunting grounds along the Atlantic arm of the western flyway, was threatened with extinction.

The Ortolan bunting has mainly been caught with a single-catch cage trap called matole (picture on right).

The single-catch principle is exceptionally inefficient and this fact, combined with the short migratory peak at Landes (about a week at the beginning of September), makes the catch results seem grossly exaggerated.

Leading French ornithologists in the 1950s most likely had the explanation for this apparent contradiction, which falls in line with information from Cyprus.

In 1953 Noel Mayaud, a member of the editorial committee of Alauda, the scientific journal of the French Ornithological Society, wrote in a letter:

"Even today, in the southwest (Landes), the Ortolan bunting is caught in nets together with a number of other small birds also called ortolan".

The same year another French ornithologist, Robert-Daniel Etchecopar, wrote:

In the south of France we continue to use this term - ortolan - but the fact is that it denotes any small bird we put on the plate. The Ortolan bunting maintains its culinary prestige, but the reality is that the word no longer has any special meaning.

Based on these facts, the claim that the recent hunting of ortolan bunting in France was unsustainable was apparently built on erroneous empirical hard data. The proportion of ortolan buntings in bird catches across Europe during several hundred years shows that hunting and trapping has had no effect on its mortality rate.

Create Your Own Website With Webador